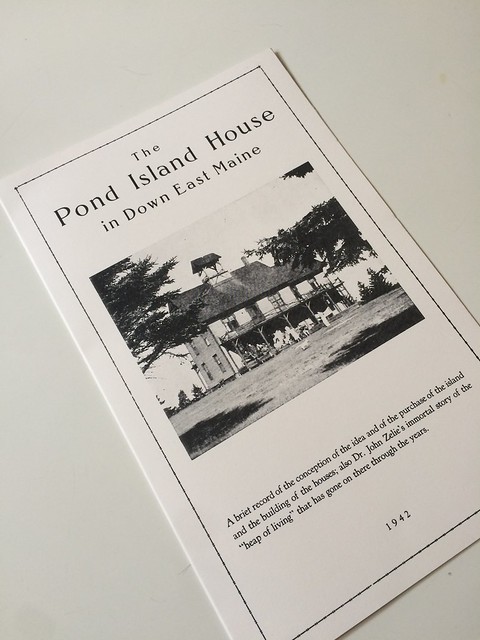

I grew up hearing stories about the island -- a faraway place, nearly impossible to get to, accessible only by chartered fishing boat or in dreams. My Nana spent her childhood on the island, hunting for arrowheads with her cousins, her hands stained from wild blueberries collected just before.

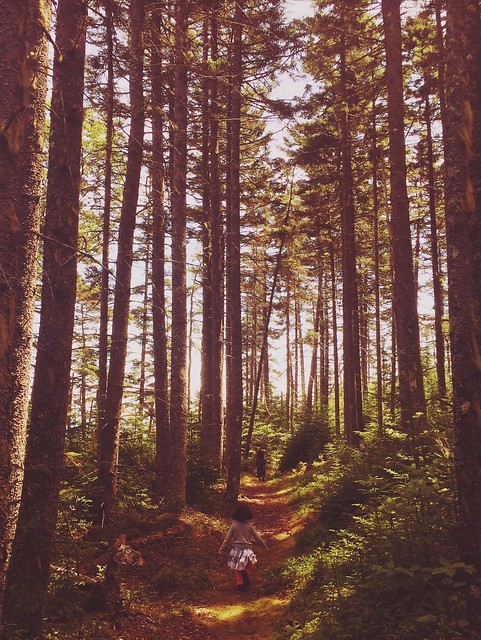

Pond Island was like a myth to us as children. We drew pictures of the Big House in our heads and dreamt of tromping through the woods, berries in our pockets, fairies in our periphery.

Pond Island was like a myth to us as children. We drew pictures of the Big House in our heads and dreamt of tromping through the woods, berries in our pockets, fairies in our periphery.

***

We are the last to arrive by boat. The kids clutch their backpacks and Hal holds onto the suitcase we have filled with our clothes for the next three nights and four days. The bay is freckled with lobster cages and we wave at fishermen and clutch the arms of our chairs. Every time I find myself in Atlantic waters I feel as if I'm having an affair with a ghost. California is a sandy-haired child compared to Maine's gray fog and bearded coastlines. To grandmother's house we go... Or perhaps, more accurately... To grandmother's grandmother's cousins' house we go.

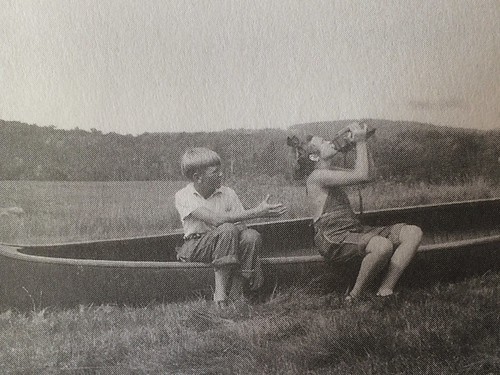

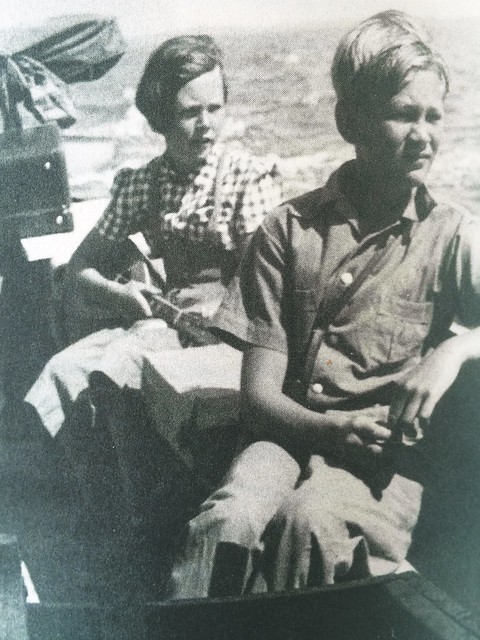

Uncle John and Nana, Maine - 1936

"Pond Island is just around that corner," the captain tells us. "You see that house?"

We do.

Bo and Fable, on the boat to Pond Island, 2015

We see the house and soon enough, we see our cousins, too. They wave to us from the shore. My parents and my brother and his wife, my sister and aunt and cousins and my grandmother with her canes in the air.

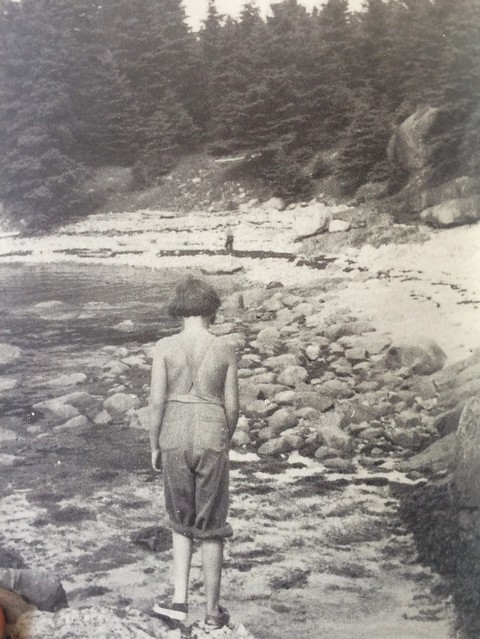

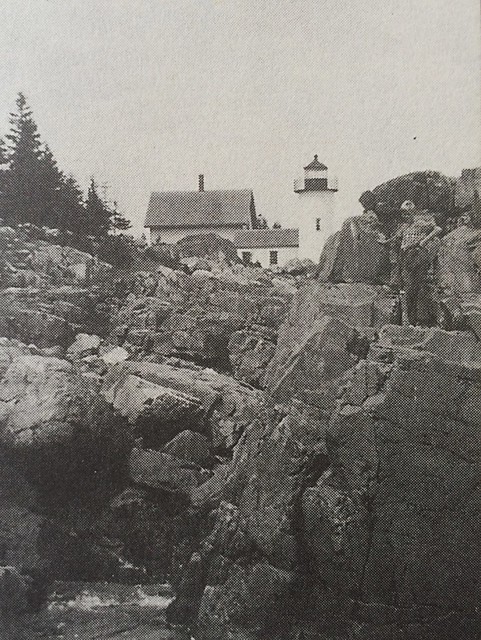

Uncle John and Nana arrive on Pond Island, 1939

There is no dock so we exit into the water, passing our babies down the line so that they don't get wet. The water is cold against our ankles. We're here. I can't believe we're here.  I dreamt about this once.

I dreamt about this once.  And this.

And this.

There is a tractor on the other side of the rocks and one by one, we drop our luggage on the back. We hold hands and begin the walk up toward The Big House, where all 20 of us will be staying. Eight children. One matriarch. Four generations...

***

My Nana grew up coming here. So did her father and grandmother all the way from Yorkshire.They were the English component of the clan. And although my great-great-grandmother was an American who married an an Englishman, my family on my mother's mother's side didn't re-settle in America until later on, when my Nana's parents split and my great-grandmother moved with her new husband to a farm in Pennsylvania.

Nana's mother, Ruth, via an article she wrote about farming, Vogue Magazine, 1942

***

Lady Hattie was the name of my Nana's American grandmother. Hattie was a suffragette who devoted her life to women's causes. She was a prime mover in the Girl Guide (Girl Scouts) movement, served as President of the National Spinster Pension Association (which fought so that single women could be eligible for health insurance) and assembled the first family planning clinic in Halifax, Yorkshire.

Hattie is our tie to the family in Maine, all distant cousins who own fractions of the island -- purchased in the late 1800s.

Hattie is our tie to the family in Maine, all distant cousins who own fractions of the island -- purchased in the late 1800s.

***

She is why we're here, I think. Because of Lady Hattie. I can feel her ghost kicking across the shore the moment we set foot on the island. The energy is palpable in the rubble of old paths. We cover ourselves in the dust of many generations as we pull ourselves toward the fields.

We are mainly women on this side of my family. Archer and my brother are the only male blood relatives, here. My grandmother has two daughters who had four daughters (and a son) who had seven daughters and one grandson.

My brother, David, and Archer high five in solidarity, form an alliance and lead us toward the makeshift bridge which stretches through the wooded bog en route to the Big House.

We are mainly women on this side of my family. Archer and my brother are the only male blood relatives, here. My grandmother has two daughters who had four daughters (and a son) who had seven daughters and one grandson.

My brother, David, and Archer high five in solidarity, form an alliance and lead us toward the makeshift bridge which stretches through the wooded bog en route to the Big House.

"Welcome to Pond Island," we say to ourselves, tightrope walking through trees.

We hold our hands out for balance as mosquitoes bite our ankles.

We hold our hands out for balance as mosquitoes bite our ankles.

"The Big House" appears at the end of the clearing. It looks like a dollhouse with its yellow sides and wrap-around porch. Its roof is in the process of being mended, but for the most part, the house looks exactly as it has for the last 120 years...

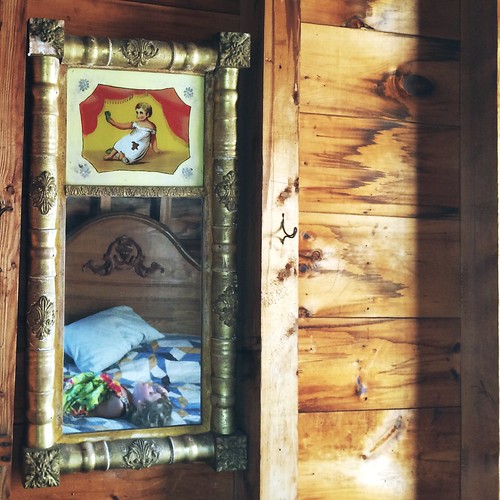

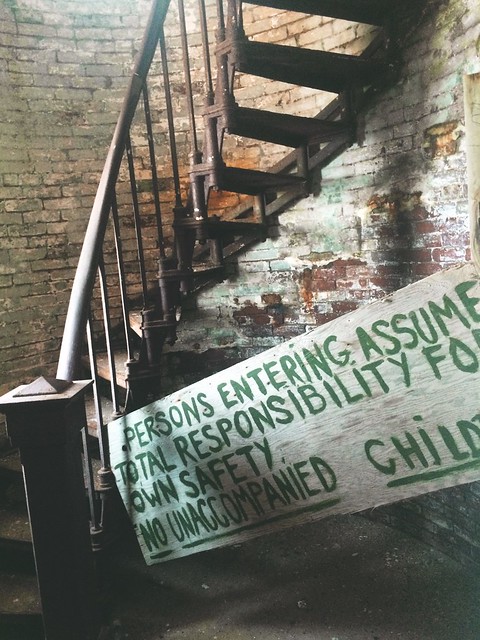

The house is smaller than I expected but on the inside it feels huge and I get lost upstairs and then again, in the attic, on the way up to the roof...

The house is smaller than I expected but on the inside it feels huge and I get lost upstairs and then again, in the attic, on the way up to the roof...

The rooms have not been updated. Not in decades. There are bedpans in each room and a pump for water in the kitchen. We drink from the well on the other side of the woods. We use an outhouse--there is no indoor plumbing here--which is located 100 feet from the house. There are holes in the floorboards where, tomorrow night, Bo and Revi will drop their toothbrushes on my dad's head.

We have brought our own food and supplies and planned a menu for each night. One for the children and another for the adults. There are two generator-run refrigerators and two gas stoves in the kitchen, and a large common area with two large tables. There are games and cards and puzzles and books and the walls are freckled with old art and artifacts. It feels like camp, here. We sit down together and pass the wine.

There is a view from every window. The sea surrounds us. So do the rocks and the strawberry fields overflowing with tiny fruit and crickets that leap out from under the dozen pairs of bare feet running toward the shore...

It feels like second nature being here. The rest of the world feels esoteric in its farawayness and all at once I understand why people up and run away... move to the woods, throw their phones into the sea. Everything feels connected in a disconnected world... Like losing one sense in place of all the others... I can see more clearly, here. I can hear every sound.

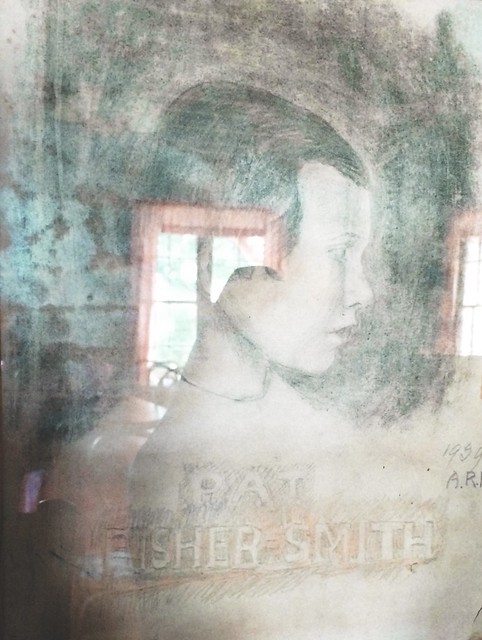

There is a drawing of my Nana as a child that hangs in the hall. And memories of her childhood spilling out from her mouth at all occasions. We follow her around like dogs and collect the scraps of stories... of cousins and collections and castaways. (My favorite story is about my Nana and her cousins building a makeshift boat and sailing away to another small island across the way... and getting stuck. On the other island. By themselves.)

There is a drawing of my Nana as a child that hangs in the hall. And memories of her childhood spilling out from her mouth at all occasions. We follow her around like dogs and collect the scraps of stories... of cousins and collections and castaways. (My favorite story is about my Nana and her cousins building a makeshift boat and sailing away to another small island across the way... and getting stuck. On the other island. By themselves.)

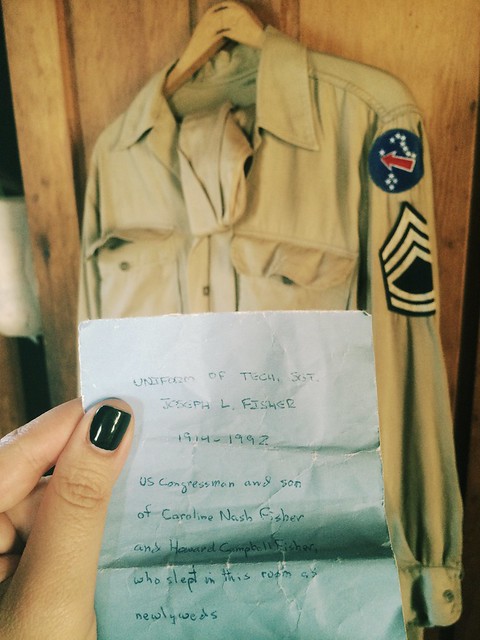

Every bedroom in the house reveals a new clue to past generations. This house is like sleeping in a family tree, recognizing branches we didn't even know existed. I feel both estranged and connected to every name I read and every note I find, folded inside drawers and in the pockets of old uniforms...

The uniform of Sgt. Joseph Fisher

1914-1992

US Congressman and son

of Caroline Nash Fisher and

Howard Campbell Fisher

who slept in this room as newlyweds

I collect everything I can find to remind myself of this moment. I write it all down. I take a thousand photographs. I inhale every seam. I look for clues behind picture frames.

The six of us share one room. The kids are in sleeping bags and we're in a bed that sinks when you sit on it. None of us know how old these beds are but the bedding is yellow and the mattresses resemble deteriorating museum pieces. But, like, in the best possible way...

After settling into our rooms, we spend the rest of the afternoon picking berries, catching crickets, and exploring the island...

It gets dark very fast on the island and before we know it, the upstairs floors are pitch black. There are enough headlamps to go around and I have brought glow sticks for every night we are here, assuming the kids will be afraid of the long pitch black hallways and corridors...

I'm wrong. They are not afraid. They are overjoyed. By their shadows. And their bracelets and the lights they shine with their foreheads against black and barren walls.

We marvel at their fearlessness. They want us to leave them alone in the darkness. They want us to pretend to be monsters and chase them. They want to hide in an old creaky house and find their way back down the stairs by themselves.

They have each other and that makes them fearless, I think. There is strength in numbers, even when you're small. Even when you're two and three and three and four and five and six and eight and ten.

We agree to let them stay up until 9:00. 9:30. 10:00 whatever time it ends up being when we all turn in and go to sleep. There is no clock on this island. No schedule. No plan. We exist on the other side of the wall where time cannot reach us.

Every day since we've been home, Bo has asked when we can return. Some days she cries because she wants to be back on the island. She wants to be back with her cousin, Jade. She wants to be back with the crickets...

And I tell her, I'm sorry.

And I tell her, I know.

And I tell her, "Someday, baby..."

Of all the kids, she was most fond of the island. Of the forest and the field and the rocks. And every day, Hal and I said to ourselves and each other, "This is where she is happiest. This is where she is her TRUE self. This is where she belongs..."

This is Bo in her element. Barefoot in a field catching crickets for hours. And hours. And hours.

Wild thing... You belong in a field, with crickets in the pockets of my flannel. I am sorry we cannot give you that life but someday, you can have it for yourself. And in the meantime, we shall seek out as many fields as possible...

Bo didn't get any bug bites. Not one. I counted 53 on one leg alone and she didn't get a single bite.

"That's because they're my friends," she explained. "They wouldn't bite their friend."

***

*** ***

***

It's our second day on the island, so we set out to find The Lighthouse. We have a map and we have a Nana, who is fearless and willing to climb with her canes across the rock. But as paths get less path-like, we start to doubt whether we were going in the right direction. We think we are and then we're not quite sure and then we feel totally lost...

And then, as we're all second-guessing ourselves -- turning maps upside down and feeling frustrated--the lighthouse reveals itself. Aha, we think. OF COURSE!

When you are in need of a lighthouse and it has yet to appear, keep walking. Because, eventually...

The lighthouse is haunted. There was a fire nearly 100 years ago and the lighthouse keeper's wife and children were killed. It was horrific and we didn't tell any of the kids. But they knew... something.... It all felt very something-ish...

The lighthouse has been out of use for many years. And yet, inside, it smelled like roses. Like rose perfume. Like someone was there. We were certain someone was there...

Later that evening, my dad gathers the girls around him and tells stories. And they listen and laugh and ask for more. There is a picture in my head that looks a lot like the ones below -- it's of my father, outside, with the girls hanging off his shoulders and his knees... asking him what happened after the purple storm.

"You want to know what happened after the purple storm?" my dad asks.

"You want to know what happened after the purple storm?" my dad asks.  "... A rainbow appeared..."

"... A rainbow appeared..." "And it stretched across the island so that everyone could see it."

"And it stretched across the island so that everyone could see it."

My dad's story wasn't pure fiction. There was a storm while we were there. There was also a rainbow that stretched across the island. There was swinging and playing and chasing and tagging and falling and crying and laughing and taking sweaters off and putting them on and taking them off, again... There was US just being. Together and apart... alone... all of the above. Under the rainbow.

Nana. Pond Island, 1939

Nana. Pond Island, 1939

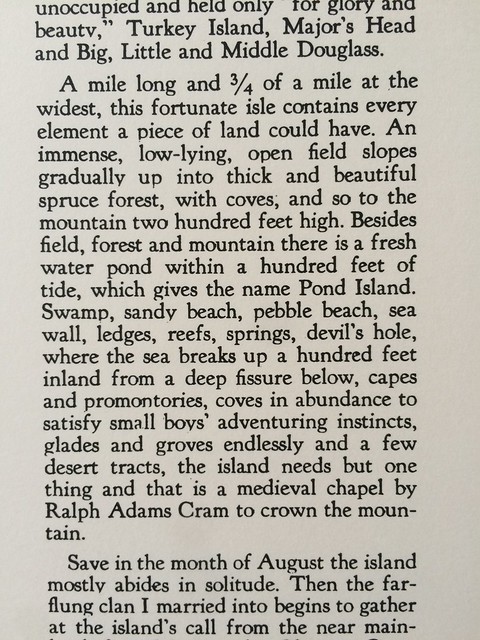

In the Pond Island Pamphlet, of which we each received a copy to take home, author/relation John Zelie (circa 1942) writes:

An island has a genius of its own which cannot be forced but only waited upon. Its best work is done months after you have forsaken it. Then along about February when the year drags, or as Thoreau puts it, creaks on its axle," and the city and the neighborhood hamper and pinch, you say to yourself some night, "Oh, if I were only on the island tonight with a roaring fire and the surf without, I could do something." You know perfectly well that water would freeze within ten feet of the fire and that all the bungalow blankets would not keep you warm. But be not ashamed of your thought. Treasuring your delusion, you go up to your room. The island now begins to do its work and in some mysterious way throws around you all the separation and detachment you crave. It has kept its inspiration for your hour of need. The city, the street, the neighbors, the house-hold fade away. Never were you so truly on the island as now. Now comes night after undisturbed night of "toil unsever'd from tranquility." The island which would never allow itself to be "rushed" is now all attention and serviceableness and interposes layer after layer of detachment and protection between you and the world which is too much with us.

(Amen.)

(Amen.)

On our way to catch the boat home from the island, we take the long way to shore -- around the bog and through the clearing in the woods. (Most of us had been bitten up so badly we couldn't bear to subject what remaining skin we had left to more mosquitos... )

(Indeed it has. Thank you, Frank.)

(Indeed it has. Thank you, Frank.)

I grew up hearing stories about the island -- a faraway place, nearly impossible to get to, accessible only by chartered fishing boat or in dreams.

For our children, though, that will not be the case. Pond Island is now a real place that exists in the seams of their memory.

And they will grow up telling stories about the island -- a faraway place, nearly impossible to get to, accessible only by chartered fishing boat or in dreams. They will talk of the time they spent their days hunting for arrowheads with their cousins, their hands stained from wild blueberries collected just before. They will draw pictures of the Big House in their notebooks. They will know what it is to tromp through the woods as children, berries in their pockets, fairies in their wake. And whether or not we return next year or ten years from now or never again, I am so incredibly grateful for that.

0 comments:

Post a Comment