One day on Pond Island after breakfast when I was ten years

old, my father, Emerson Fisher-Smith, turned to me and asked, “How would you

like to go painting with me?” The day before, he and three other men lined up

their easels in front of the Big House and painted the same view in oils. I was

pleased Dad chose me for a companion the next day, especially when he said he’d

like us to paint a giant blue spruce on the edge of the trail to the

lighthouse. Nearby was a fallen tree trunk where Dad and I could sit

side-by-side and in front of us, between the tree and our fallen log was a

small clearing where the ground rang hollow under foot. Older folks swore there

was a treasure chest buried there, perhaps by pirates. Someday they meant to

dig it up, but no one ever did.

Dad had

brought watercolors for each of us in a blue denim bag stuffed with everything

we needed.

“First, study

the scene in front of you,” he said. “Put your fingers together like this and

compose your picture.” He made a square with his fingers and peered through it with

one eye. “Look at that tree on the left with its flat top, thick trunk and few big

branches with blue sky between them. See the green grass at the bottom of the

view, the clearing in the middle, the bushes and trail through the woods on the

right.” He showed me how to put the tree above the foreground and on one side.

“Now,” he said, “Draw it as well as you can.”

When I was

done he said, “Good!” unscrewed the top of his old army canteen and poured

water into a jar for me and another jar for him.

“What’s the

lightest thing you see?” he asked.

“The sky?”

“Correct!”

said Dad, “So mix up a big puddle of blue on your palette and paint your sky

first. With your left hand, hold your painting upside down and begin painting at

the horizon and work your wet paint quickly all the way to the top of the picture,

which is pointing down. That way the sky will always be lighter at the horizon

and darker above, as it is in nature.” As Dad talked he demonstrated on his

painting, but never touched mine.

“Dry your brush on your paint rag and use it

to wipe off the excess paint from the top of the sky. Then you can put your paper

right side up again and lay it flat. Now don’t touch it again until it’s dry.”

“I’ll show

you how to paint clouds another time,” he said. “Just remember with watercolors

you leave bare paper where you want something to be white and you always paint

from light to dark. Oil paints are the opposite. So, now, tell me? What’s your

next lightest thing?”

“The grass!”

I said.

“Yes,” said

Dad, “so paint the light green foreground next since it doesn’t touch the sky. That

way they won’t run together and spoil your painting. Always let each area dry

before you allow another wet area to touch it.”

It took us

most of the morning to finish our paintings. Dad showed me on his painting how

to do each step. When all the areas looked finished and had dried, Dad

said, “Now point to your light source.” I

pointed at the sun, straight up but a little to the left.

“Okay,”

said Dad, “So where are the shadows?”

“All over

the place.”

Dad

laughed. “You’re right but I’ll give you a little trick. If the sun is overhead,

just choose the direction of the light when you began and paint your shadows on

the opposite side. Mix Ultra Marine Blue with Burnt Sienna and you’ll get a

beautiful gray. Paint that onto the right-hand side of your tree trunk and shrubs

and under the branches and foliage and use it to make a patch of shadow on the

ground under the tree but mostly on the right.”

When I’d

finished I was excited. Dad took my painting and propped it against a bush so I

could see it at a distance.

“That’s

really good,” said Dad. “Now sign it down here on the right.” I carefully penciled

“Pat Fisher-Smith”.

Dad told me

to bring my painting to dinner that night and show it to the grown ups. They

oohed and aahed. The cousin we kids called “Aunt Bess” pinned it on the wall,

where it stayed all summer. Years later another cousin about my age said, “They

made such a fuss over your painting, but I didn’t think it was all that good.” It

probably wasn’t, but no one told me and that gave me courage to continue.

When I was

a kid I had two dads encouraging me to paint. My other father figure was my

eccentric stepfather Geoffrey Morris, fashion photographer and avid gardener.

He gave me art supplies every year for Christmas. I put Geoff in one of my books. Geoff was far more fun to write about than to live with, but in more than one

respect he had a positive influence on my life. When I was 13 Geoff said, “You

can’t paint well without first learning to draw well. If you learn to draw the

human figure, you can draw anything. “ For Christmas that year he gave me a

book called “Anyone Can Draw,” by Arthur Zaidenberg.

That book taught me to draw.

At ScrippsCollege I majored in English but studied watercolor with Millard Sheets and oilswith Henry Lee McFee. Then, six weeks before I graduated I went on a blind date

and met a wonderful man, a Los Angeles lawyer called Louis M. Welsh. Before

dinner that evening he engaged me in a one-hour conversation. At the end of it he

proposed and I accepted. Six weeks later on my graduation day we were married. Soon

I had a family, house and garden to care for. There was no time to paint. It

wasn’t until we began taking vacations that I struck on a solution. While Lou

took a nap or read a book after lunch, I had time to paint a watercolor. Lou

loved my paintings even when I didn’t. After he died I forgot how to paint, but

finally got it back.

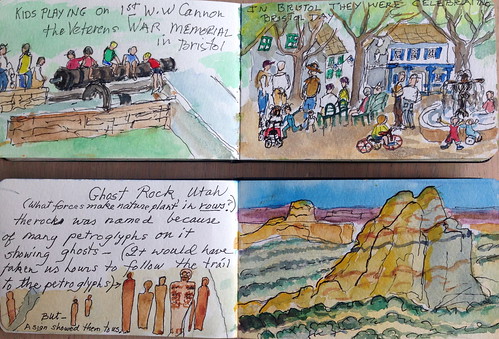

These days

I paint in oils in my garden with friends and family, but when traveling I stick

to watercolors and pen and ink. I wear a photographer’s vest with pockets carrying

a drawing pencil, pencil sharpener and eraser, a 3”X5” Moleskine™ notebook withwatercolor pages, and a Winsor Newton Professional Traveling Paint Kit with a

paint rag wrapped around it secured with a rubber band. (Professional paint is

more expensive than student grade, such as Cotman, but it’s worth it.)

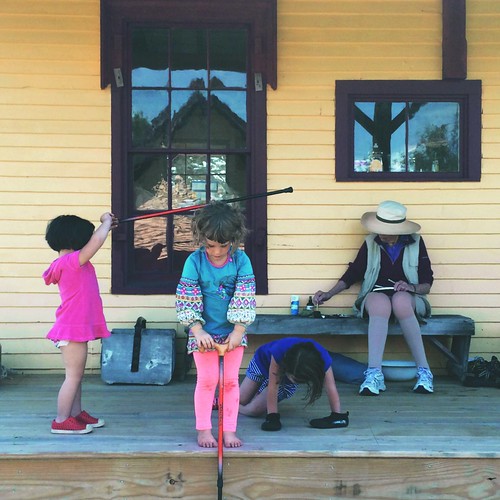

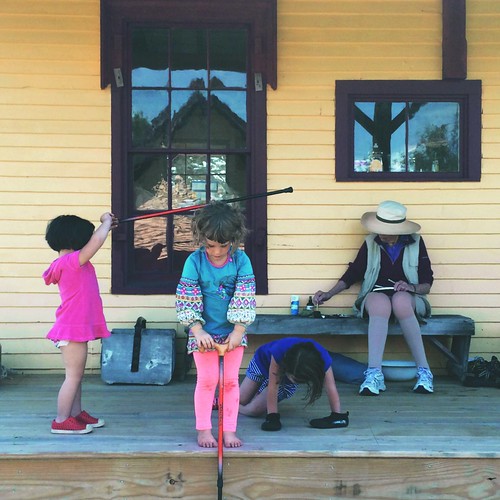

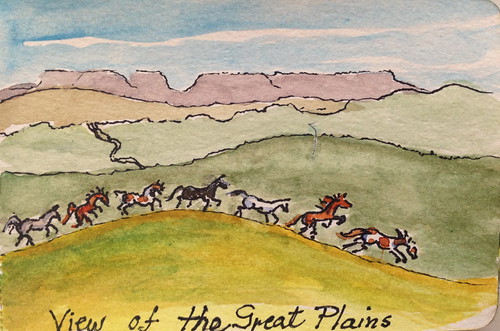

Painting on Pond Island this past summer

I also

carry 1 or 2 fine Pigma Micron Archival Black Ink pens. (The ink in this brand

does not run when one paints over it.)

Painting on Pond Island this past summer

I also

carry 1 or 2 fine Pigma Micron Archival Black Ink pens. (The ink in this brand

does not run when one paints over it.)

Painting on Pond Island this past summer

Painting on Pond Island this past summer

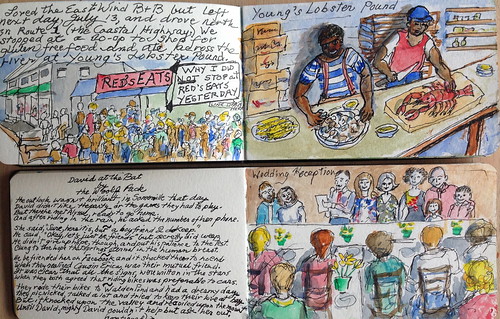

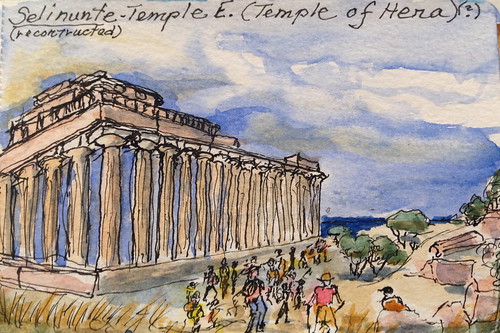

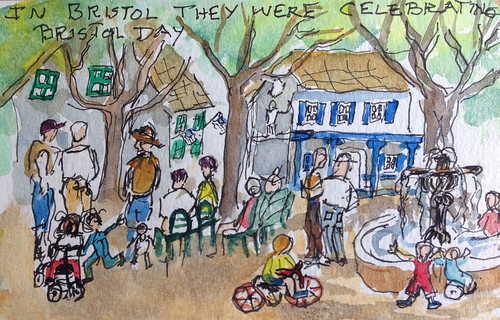

Instead of taking

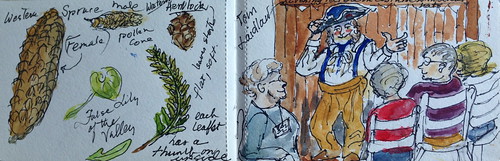

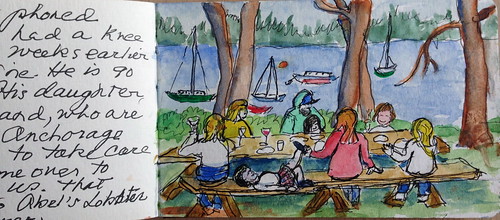

photos as I travel, I make quick sketches in pencil, improve them in ink, and

paint them immediately if time permits, later if not. I paint on the right hand pages and write

notes facing them. These Moleskine™ sketchbooks are a lasting pleasure, a

record of my travels, inspiration for oil paintings, and source of many

friendships.

sketching in Starksboro, Vermont

People ask me where I get my equipment. They tell me they want to

do the same or pass on the idea to a wife, child or friend. Watching me churn

out these little pictures makes folks realize it’s not all that difficult.

sketching in Starksboro, Vermont

People ask me where I get my equipment. They tell me they want to

do the same or pass on the idea to a wife, child or friend. Watching me churn

out these little pictures makes folks realize it’s not all that difficult.

sketching in Starksboro, Vermont

sketching in Starksboro, Vermont

So thank

you, Dad, for spending that magical morning teaching me to paint. I still turn

my watercolors upside down and paint the sky first. And thank you, Geoff and

Lou, Millard Sheets, and Henry Lee McFee. All through the years my love of

painting that began on Pond Island when I was ten years old has remained an

integral part of my happiness and passion for life.

0 comments:

Post a Comment